By Sterling Allan

From PHN Issue 55, Winter 2024

Note from PHN editors: This article is specifically about managing type 1 diabetes, which is an autoimmune problem usually diagnosed in childhood or early adulthood. The author has a lot of experience managing his sugars. What works for him might not work for everyone.

Here in prison, I was able to maintain my A1C in the “normal” range for four years, despite how difficult it is. My purpose here is to share some key takeaways I’ve learned the hard way, so you can benefit from my pioneering efforts without the difficulties.

First, let me say that I no longer target a “normal” blood sugar average, which is 100 mg/dL on the glucometer. My motivation has come from what my doctor told me when I was first diagnosed as a type 1 diabetic two decades ago. He said I could live a full life if I maintained good control of my blood sugar.

The problem with shooting for a 100 average is that it means skirting dangerous lows to balance the highs. When I learned that going dangerously low results in brain cells diminishing, I changed my strategy. That is a terrible downside that is unacceptable to me. So, two years ago, I changed my target to 150, which is about an A1C of 6.8%. I’m confident that this is still in a range that can result in a full life, unimpaired, but it averts the dangerous lows.

I’ve not had a single incident since the time I had three incidents requiring dextrose injections in three weeks with an A1C of less than 4.8%. I’ve had other less severe episodes where my sugar got too low … I had to eat five oranges once to counteract this. I’ve not lost consciousness, whereas when I targeted 100, I would have one or two such incidents per year on average (here in prison). Now, rarely do I go low enough to trigger my body’s emergency release of glucose from the liver via glycogenolysis. My typical fluctuations range between 80 and 300. Extremes are 50 or 400 and are rare. My present two-week average of readings on my glucometer is 153, very close to my 150 target.

Here are some principles that serve me well:

- Don’t eat until after you get insulin (unless you are low and need to eat enough to get back on target).

- Know approximately how fast your blood sugar drops after getting fastacting insulin (mine drops about 125/hour).

- If your blood sugar is high (e.g., above 150) before eating, you might need to increase your fast-acting insulin to keep your sugars in a normal range.

- Injected insulin doesn’t release all at once but is more gradual, tapering off after about 3.5 to 4 hours. If possible, don’t eat the meal all at once, or eat slowly. Eat the main carb first, wait half an hour, then eat the second-level carb, wait half an hour, then eat the next item.

- Realize that different foods take different lengths of time to become glucose in the blood. Here’s what I found by paying attention (I have rigorous notes):

- Fruit takes ~ 15-30 minutes

- Honey, syrup, and sugar take ~ 10-15 minutes

- Wheat takes ~ 30 minutes

- Oatmeal takes ~ 2 hours

- Corn takes ~ 2 hours

- Rice takes ~ 3 hours

- Protein (e.g., nuts, peanut butter, eggs, cheese, meat, milk) takes ~ 5 hours (some of the amino acids, if unused in muscle repair/ building, turn to glucose)

- Beans take ~ 1 hour

- Veggies take ~ 30 minutes (some don’t have much glucose, especially salad and broccoli, but veggies like sweet potatoes and beets have more sugars)

- Understand approximately how much glucose comes from typical food/dish servings.

- The proper long-acting-insulin dose objective is to hold the blood sugar level steady after the short-acting insulin has worn off. The best time to check this is late evening, about 4-5 hours after the PM insulin administration.

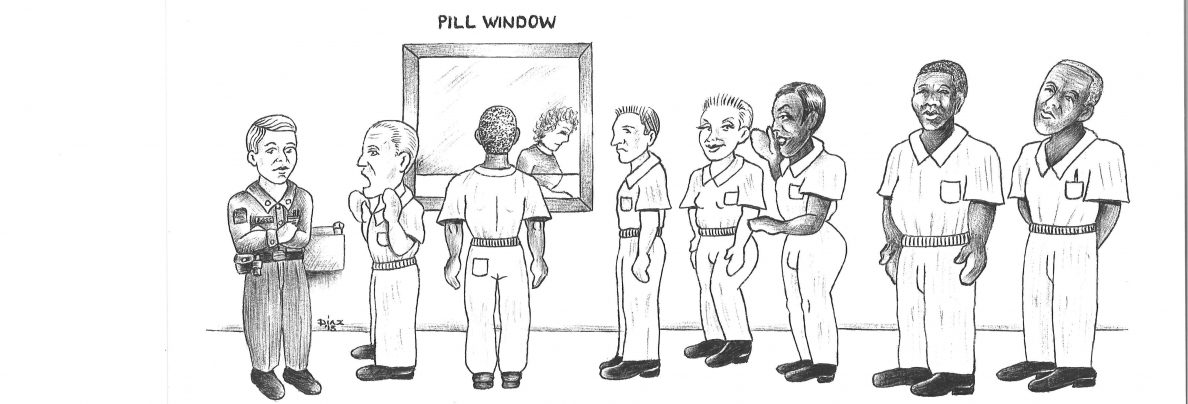

- If your prison only administers insulin 2 times per day (as is the case here), have your doctor refer you to an endocrinologist if necessary to get it 3 times per day, one for each meal, and allow a two-time dose at PM if noon doesn’t arrive for some reason.

- Keep an insulin log to track things.

- Check your sugar level at least 6 times per day to know what’s going on. I check mine quite a bit more than that. Data is important. You don’t drive a car blindfolded.

- In interacting with the medical staff, be confident, kind and friendly, but don’t overdo how good you are at this, as that tends to backfire.