By Wayne Thomas

From PHN Issue 52, Spring 2023

There is an increasing restriction of constitutional rights and other safeguards on people with mental illness in prison. The punishment of individuals with psychiatric problems in prisons might affect the perception of people impacted by mass incarceration.

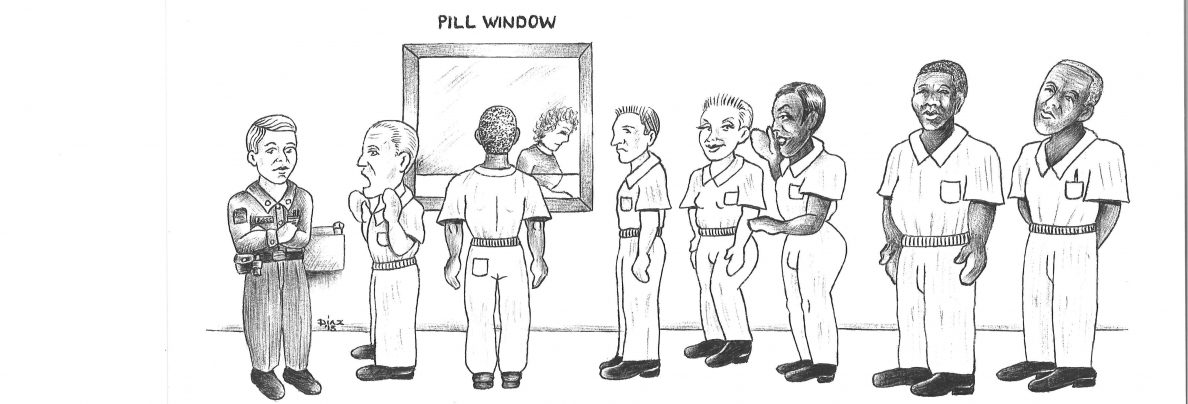

We are troubled by the punishing of people who suffer from mental and emotional disorders, who are often forced to take antipsychotic drugs during the trial or pretrial setting. There are a large number of instances in prisons and courthouses when a person with mental illness is forced to take medications against their will. The person is incapacitated by being put in a medication-induced stupor and then removed to a courtroom where they are sentenced to a term of incarceration. This is a process that maintains physical control over the mentally ill persons, forced by law to subject themselves to take antipsychotic medications when released. Often they are threatened with the possibility of return to confinement—to ensure medication adherence for formerly incarcerated people who are categorized as mentally ill.

Incarcerated people with serious mental illness are forced to remain dependent on the state to maintain access to therapy services and medications. In many of these settings, the outpatient care is haphazard, perfunctory, and utilizing treatment methods that do not bring about functional recovery for the individual when released back into society.

Here is an example of the kind of dilemma we face in the Pennsylvania court subsystem. In the ’60s, the National Institute of Mental Health and the Justice Department-funded research to develop socialization biomedical controls (i.e., brain surgery, genetic theories, and behavior medication, to name a few). These objectives were adopted in 1992 by Dr. Frederick Goodwin, formerly head of the U.S. Health and Human Services Department’s Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration, whose purpose was to control certain psychological behaviors of people in certain cities. (The City Sun, New York, NY, December 15-21, 1993). The program Goodwin proposed was later shelved. Because of his remarks, he was demoted down to head of the National Institute of Mental Health. Now carrying on the same repressive legacy is E. Fuller Torrey, another notable psychiatrist of the same National Institute of Mental Health as Dr. Goodwin. It is suspected that huge sums of grant funds through Torrey go to the Alliance for the Mentally Ill of Pennsylvania, under the umbrella of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and Torrey’s project to initiate mandatory medication treatment centers and halfway houses for mentally ill people who are incarcerated in Pennsylvania.

The medicalization of people in prison has two big impacts: One is forcing medication on people released from prison; and another is the sale of medicines now being marketed to the criminal justice system.

There is a broad legislative arena of social policy change that is needed to protect citizens as well as incarcerated people against the dirty work of forcing psychiatric meds on us. Social resistance protesting cannot be limited to only one segment or another (say, the academia/consumer/survivor “community organizers”) of the mental health system, but should be a part of engaging political actions on behalf of all citizens who are victims of an oppressive psychiatric system.