By Hannah Calvelli and Dan Lockwood

From PHN Issue 52, Spring 2023

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) is a term used by addiction and medical professionals when referring to the three medications (buprenorphine, naltrexone, and methadone) that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of opioid use disorder. You may have heard of Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT), which is a similar term that refers to the use of FDA approved medications for both alcohol use disorder and opioid use disorder. The difference between MOUD and MAT is that MAT is part of a larger treatment and recovery plan that includes counseling and behavioral therapy, whereas MOUD is treatment with medications only.

Opioid use disorder is a medical disease. Like many other diseases, treatment can help patients get healthy and stay healthy. MOUD helps people stop using opioids and decreases the likelihood of relapse. In doing so, it also has the following benefits:

- MOUD reduces the number of deaths that occur due to opioid overdoses

- MOUD can help people gain/maintain employment when used in combination with re-entry programs

- MOUD lowers the risk of contracting diseases that are spread through sharing needles used to inject drugs, such as HIV and hepatitis C

- MOUD improves health outcomes for pregnant people and their babies

- MOUD makes it more likely that people in jail or prison will engage in treatment after release

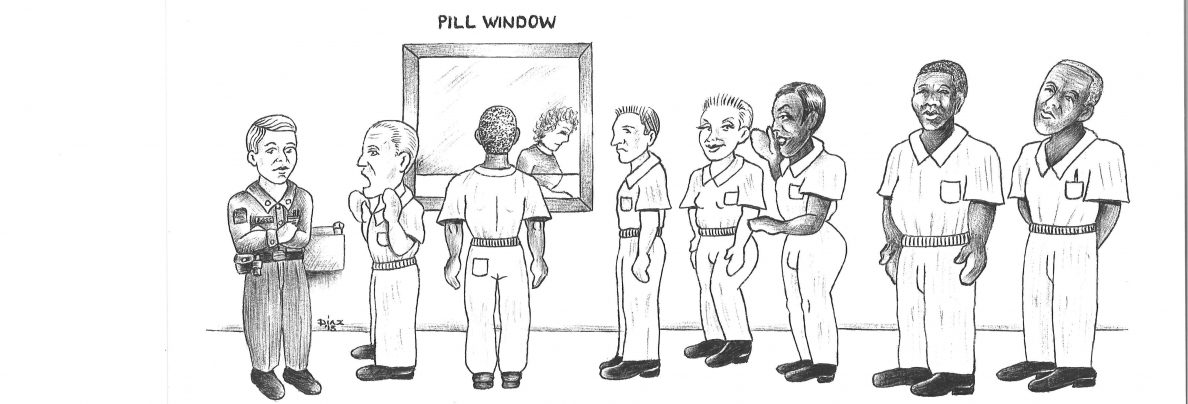

Opioid use disorder affects many people within the carceral system. It is estimated that around 1 in 5 people who are incarcerated have an opioid use disorder. However, opioid use disorder often goes untreated. The American Society of Addiction Medicine reports that medication and counseling should be the standard of care for individuals with opioid use disorder in criminal justice settings. Despite evidence that MOUD saves lives, the vast majority of jails and prisons do not offer this treatment. Some reasons for this include lack of community support and specialists, stigma about the medications, statewide restrictions, and cost.

According to the 2020 PEW research report on opioid use disorder in jails and prisons, there are steps policymakers should take in order to ensure MOUD is implemented more widely across carceral settings. These steps include:

- Providing resources and introducing policy changes to help jails and prisons offer medication and counseling for opioid use disorder and help people transition to community-based care as they leave incarceration

- Requesting data from state agencies to understand the nature of the substance use and treatment needs of individuals who are incarcerated

- Funding integrated data systems that allow for health information exchange and care continuity across different settings

- Setting aside funding to screen anyone who is incarcerated for opioid use disorder, provide MOUD and counseling, and ensure adequate data gathering and personnel to track MOUD treatment outcomes

There are currently three FDA approved MOUD medications for opioid use disorder. They are buprenorphine, naltrexone, and naloxone. The way each of these medications work is by acting on the opioid receptors in the body. These receptors are like docking stations that control the release of chemicals in the brain. When people take opioids, the receptors get stimulated (turned on) and chemicals get released. This is what causes the “high” of opioid intoxication.

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is what’s called a partial opioid agonist. This means that it stimulates (turns on) the same opioid receptors that normal opioids do, but with a weaker effect. Because of this, buprenorphine can help people become less physically dependent on opioids because they don’t have the same level of cravings and feel the same “high,” since the receptors aren’t being turned on as much as if they were to take heroin, fentanyl, or another opioid. Buprenoprhine also decreases the chances of having an overdose. It is often combined with naloxone, but some prescriptions contain buprenorphine alone. It comes in the form of tablets, sublingual films (goes under the tongue), buccal film (goes in your cheek), implants (goes under the skin), and extended-release injections. Each of these forms has a different name, so you may have heard of buprenorphine referred to as Suboxone, Subutex, Sublocade, Probuphine, Zubsolv, or Bunavail. People should not take buprenorphine if there are still opioids within their system because they can go into withdrawal. It is possible to overdose if you take too much buprenorphine because it still has some effect in turning on the opioid receptors. Being on buprenorphine requires working with a medical professional to adjust and find the right dose for you.

Naltrexone

Naltrexone is what’s called a full opioid antagonist. It also acts on the opioid receptors but acts to block them (turn them off) instead of stimulate them (turn them on). In doing so, it doesn’t produce the “high” that opioids do and reduces cravings. Also, if people take opioids while taking naltrexone, they will not experience the “high” because the receptors are turned off. It is taken in pill form or as an extendedrelease injection. Only the injection form is FDA approved for opioid use disorder. Like with buprenorphine, people should not take naltrexone if there are still opioids within their system because they can go into withdrawal.

Methadone

Methadone is what’s called a full opioid agonist. It stimulates (turns on) the opioid receptors in the same way that opioids like heroin and fentanyl do. However, it acts much more slowly, and in doing so, doesn’t produce the same “high” or lead to the same cravings. Methadone is available in liquid, powder, and diskette form. Because it acts like normal opioids, it is considered a regulated substance, meaning that only certain places are allowed to prescribe it and it has to be taken in a supervised setting. It is possible to overdose with methadone because it turns on the opioid receptors, but it is overall a very safe medication when taken the correct way as instructed by a medical professional.

Access to MOUD varies by state. According to the 2022 report by the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project, there are different MOUD policies and practices across the 62 county jails in Pennsylvania:

- 15% (9 of 62) of jails offer no MOUD at all. This means that people cannot get any of the three medications and have to go through withdrawal in jail

- 18% (11 of 62) of jails offer MOUD to pregnant people only. Once the child is born, the person is taken off MOUD and goes through withdrawal

- 26% (16 of 62) of jails offer only naltrexone

- 26% (16 of 62) of jails provide continuation. This means that people can continue on MOUD in jail if they had a prescription for it beforehand. Continuation is also referred to as maintenance

- 5% (3 of 62) of jails provide induction. This means that people can be started on MOUD for the first time in jail

To recap, opioid use disorder is a medical disease that can be treated with MOUD. The MOUD medications may be used long-term as part of maintenance therapy in many cases, although access varies depending on where you are located. We share this information in the hopes that if you or someone else is struggling with opioid use disorder, you can be aware of these medication options and advocate for getting the care you deserve.