By Leo Cardez

From PHN Issue 50, Summer/Fall 2022

Regret runs through everything, and no man exists as he once was. People in custody have an intimate relationship with regret – left to face the suffering and damage we have left in our wake. It is as if we are stuck in a barrel at the bottom of the ocean with no options – there is nothing worse.

As a three-time loser looking squarely at middle age, I struggle deeply with my past mistakes. A list of my mistakes would overwhelm you: how I behaved as a father, brother, son, friend, and human; how I spent my money when I was working and worse, how I spent it when I wasn’t; all the dumbass things I thought were important and weren’t; all the people I hurt, especially the women who loved me most. Most of these are “closed door” regrets. That is, things that cannot be undone. There is also the opposite, “open door” regrets; those that can still be undone, relationships salvaged, minimal damage endured.

As with most emotional or psychological problems, step one is acknowledging your feelings. You regret something – accept that. Don’t try to stuff it into a hidden chamber of your heart and believe it will simply fade away. It won’t. It will rot and fester and affect you in ways you could have never imagined – none of them good. Some of us, especially hard-headed inmates, have the false belief that admitting any shortcomings is a sign of weakness. The opposite is true. Denial is like trying to put a band-aid on a bullet wound.

Regret can be a normal, healthy emotion. Painful as it may be, it is our responsibility to deal with it. Managing our past mistakes can help us become better people, better to ourselves and better to others. But how do we do that? How do we suck out the venom of the emotional snake bite?

Step one was recognizing the issue. Check. Next is sharing it with someone else we trust. I called my Mommy. My mother has been my rock – her unflinching love has kept me moored when I risked floating off forever into the darkness of a moonless night. I told her everything about my crime. I also explained how deeply sorry I was for hurting others. I am not ashamed to admit, I cried for the first time in twenty years. After patiently listening, she told me she was proud of me. What? Why? I responded. She explained, you’re finally growing up. She admitted, yes, I had made grave mistakes. I spent years wandering in the desert. But she also encouraged me to remember, no one is just a culmination of their mistakes. We all fail to live up to our full potential from time to time. She wanted me to see that my regret was an important step in my rehabilitation, and anything else would have been like trying to build a house on sand. Regret is part of the journey to redemption. She concluded by asking me to try to accept the pain as happily as the pleasures. They are both temporary and necessary.

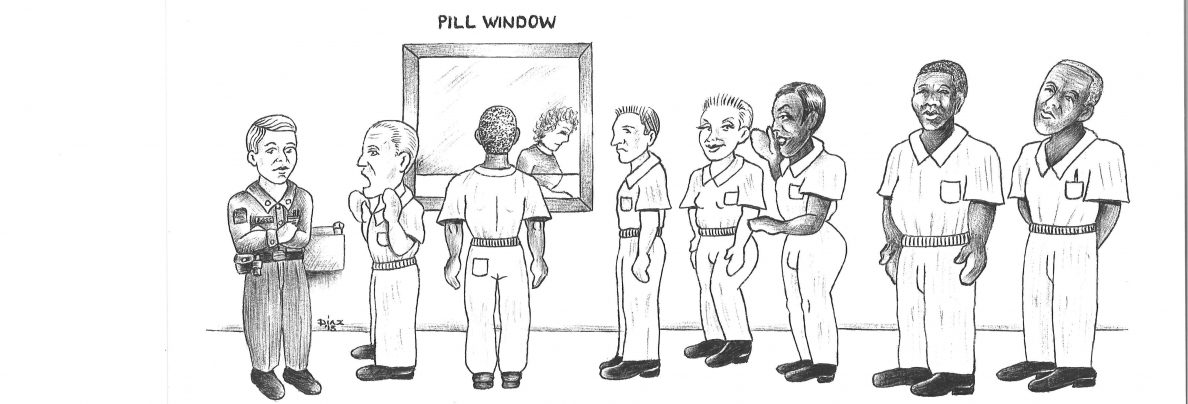

It will take a superhuman effort. It was virtually impossible for me. I hated myself. I doubt anyone could have despised me more than I did myself. I removed any mirrors from my cell as I could not stand my own reflection. But if we cannot find a way to be kind to ourselves, how can we ever expect to be kind to someone else?

The final step is to do what we can to try and make things right. In my case, I wrote heartfelt apology letters to anyone I may have harmed. Many people could not hear me past their own anger; some even chose to respond with hateful vitriol. That’s okay. Maybe they needed that opportunity to vent, even if it was at my expense. The truth is, it’s the least I could do. I also tried to get help for my problems. I attended AA and sought therapy. The point is to do something to attempt to re-balance the scales of the universe. *The only exception would be if in trying to help we cause more pain or if it’s illegal.

Now, you wait. You’ve done your best to create distance and closure from your past mistakes, but the harsh reality is that these steps are not miracles. Your feelings of regret won’t disappear overnight. But with time, effort, and a touch of grace, it can begin to shift from the feeling of something weighing you down to something propelling you forward. And then, maybe one day, you can look in the mirror and see a good person reflected back to you.

Author’s Note: The idea of my work as a mirror is important. I want to write essays that not only help incarcerated readers, but also prove to the outside world that we still have value. The goal is neither to center on the pain nor to ignore it. The full story, no matter how bleak, always has some beauty among the darkness.